Should we stop calling ourselves “evangelicals”?

Should we just give up on “evangelicalism”?

I am asked these questions all the time, usually by Christians who are concerned that these labels no longer accurately define or describe who they are and what they believe.

In this episode of Signposts, I talk about these questions and offer my own perspective on the status and future of evangelical Christianity in the United States.

Listen above, and be sure to subscribe to get new episodes of Signposts as they are released.

TRANSCRIPT

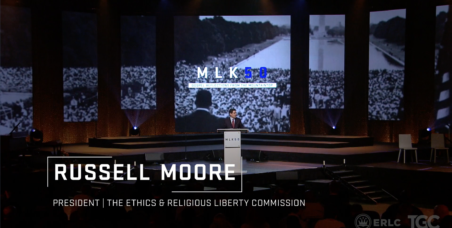

Hello, this is Russell Moore, and you’re listening to Signposts – questions about faith, life, and culture. Matter of fact, this is Signpost’s rebirth. This is the new relaunch of Signposts, and today I want to talk about a question that I get so often that I’m frankly starting to get tired of it. It’s the question of whether or not we ought to give up on the word “evangelical,” or whether we ought to give up on evangelicalism itself as a movement. Now here’s why I think this actually is an important question, and it’s about more than just names and titles and categories. I often, when I hear people talking about my hometown I know when someone pronounces it “Biloxi” that this is someone who has no idea what the town is, and they’re simply reading a word off of a page. I even had someone say to me one time, when they were talking to me about, “Now you’re from Biloxi, Mississippi.” I said, “No, I’m from Biloxi Mississippi. It’s pronounced Biloxi.” And the response was, “Well, whatever, it doesn’t matter.” Well, it does matter to me, because if you’re naming it something other than what it actually is, then it’s telling me that you don’t know it, you don’t understand it.

I think that’s one of the reasons why many of us (and I say us) are irked sometimes when we see the word “evangelical” being used in some really broad and often weird and sometimes even gospel-denying kinds of ways out there in the broader culture. A couple years ago, I wrote a piece in The Washington Post that said that I find myself not using the word “evangelical” very often anymore and instead using “Gospel Christian” when people ask me about my religious affiliation and who I am. And the reason for that is because often now, when people in the larger world use the word “evangelical,” what they’re doing is talking about mostly simply a political category. They’re talking about white evangelicals, rarely talking about evangelicals of color, and they’re talking about a caricature of evangelicals, either that’s just kind of a voting bloc – a group of people that are just kind of like cicadas that go into dormancy between Iowa caucuses every four years, or evangelical in terms of the most buffoonish sorts of representatives of evangelicalism that might be out there on television or or on the internet.

Now, why that’s important is because there is a sense out there among many people that I deal with all the time – some of you, I know that many of you who listen to this program aren’t Christians yet, and sometimes the biggest skepticism that many people have is “Well, is Christianity, and particularly evangelical Christianity, about something else? Are you talking about Jesus just so you can get me to sign up with some movement, or so that I can behave the way that you want me to behave, or so I can buy the products that you want me to buy?” Those sorts of questions. That’s a problem, that’s an important issue that we ought to face.

The other is that often when I see the word “evangelical” being used, it’s being used in a way that is on the one hand really, really narrow – talking about white evangelicals who share the same sorts of subculture, on the other hand, really, really broadly – including, for instance, prosperity gospel hucksters out there in the world that that are being claimed as evangelical Christians. And one of the ways that this came home to me in recent years was I was having a conversation with someone who is a prosperity Gospel, health-and-wealth “Christian” – and I use “Christian” in quotes here – but who was advocating all of this really, really aberrant theology, but at the same time was really upset about my denomination and my denomination’s publishing house particularly, because of the stands that they had taken on sexuality. And it didn’t make sense to me at first, because I thought “Now wait a minute, this is somebody who is a culture-warring sort of person that isn’t at all, I would think, wanting to embrace these progressive, revisionist ideas of sexuality.” Until, in the conversation, it finally started to dawn on me that this person wants to make sure that evangelicalism is not defined theologically in such a way that it would exclude the kind of product that they’re selling. I think that’s exactly what we ought to do.

So when we come to this question of “evangelical,” you see it in the newspaper, you read it on the internet, people are talking about it in your community, and someone says to you, “Are you an evangelical, are you an evangelical Christian?” Does that really matter? Well, on the one hand, no, it doesn’t matter very much because evangelical in and of itself isn’t really a Biblical word, and not only that, but very few people actually in their daily lives, I think, refer to themselves or think of themselves as evangelical. LifeWay research did a study not long ago that said there are far more people who call themselves evangelical than actually believe what one would consider to be evangelical doctrines. I know that’s true. I suspect that’s quite true. I also think though that the reverse is true – that there are many people who are evangelical Christians who don’t call themselves that you ask them “What’s your religion?,” or “What’s your faith tradition?” “I’m a Christian” or “I’m a Methodist” or “I’m non-denominational” they might say. Or “I’m born again, I believe the gospel.” I think there are all sorts of ways that people respond to that, and the answers start to narrow down when you start asking “What kind of Christian are you” or “What kind of Methodist are you? or “What kind of Presbyterian are you?” Then often “evangelical” will come forward as as a modifier.

So in one sense it’s not important, but in another sense I think it makes a huge difference. That’s especially true when we’re talking about the ways that we cooperate together as gospel Christians, as evangelicals. How do we identify the boundaries and the center of that sort of cooperation? And by that I mean cooperation in terms of things as broad as global missions, and as narrow as specific college campus ministry. I was on a campus not long ago, and it was the same story that I have faced on college campuses all over the country, where there there was a a group, a evangelical fellowship, on that campus that had to stop using the word evangelical even though they had used it for, I don’t know, 50 years. But they had to change because they’re trying to do evangelism, and when they’re talking to unbelievers what they find is that when they say “evangelical,” an unbeliever hears something very, very different than the good news of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, and the authority of the Bible, and the necessity of personal faith in Christ. They hear a specific cultural or political program. And that was impeding the evangelism and admissions thrust of that organization, and of many others that are wrestling with this and trying to figure out how to describe themselves.

Now, some people would say “Well, evangelicalism has always just been sort of cultural resentment and white identity, and those sorts of things.” Ross Douthat sort of made this argument in his column in The New York Times a couple of months ago, when he said “I’m not sure we actually have an evangelical crisis, because it could be that evangelicalism just has always been the caricature that people have of it and always will be.” I don’t believe that. I think if we look at what evangelicalism means in terms of the word itself and in terms of the movement, it’s, as Tim Keller pointed out in The New Yorker, “a renewal movement” within the church. It goes back to the revivals of George Whitefield and John Wesley and others who established, culturally established, or in some cases state established, and said “You must be born again, remember the words that Jesus gave to Nicodemus, ‘Unless a man is born again he will not inherit the kingdom of God,'” That renewal movement continues to Billy Graham, who if you’ll remember, when he’s preaching “You must be born again, you must be of the New Birth,” he’s preaching to people who were largely culturally Christian and largely, as he begins in the 1950s, a people who would share sort of homogeneous American values about life and working and family, and Billy Graham is saying “That is not good enough, you cannot simply reform yourself, you must be regenerated by the Holy Spirit of God.” That’s the gift that evangelicalism brings as an emphasis. Carl F. H. Henry, same thing. Coming in and saying “Evangelicals ought to be the people who are constantly standing up and saying ‘the gospel, the gospel, the gospel.”

So Evangelical is a good word to show the continuity of all of these different renewal movements that really are connected to one another historically and in the present. But also it’s a good word, because it’s rooted in the word for Gospel, the word for for good news, and that’s something that we really do not want to give up. As much as I’m uncomfortable sometimes with the word evangelical in the current context, we shouldn’t hastily give the word up. For one thing, the sorts of caricatures of evangelicalism that we see around us as a strictly kind of cultural phenomenon are really old and aren’t going to last. As I’ve been trying to argue for years, cultural Christianity is sick and dying. People do not increasingly just go down demographically, and look, people do not feel the need to identify themselves nominally with the church or with Christianity in order to be seen as good people.

Now at one level, that really ought to be a terrifying reality for us. Again, going back to Ross Douthat, I’m always very often reminded of what Ross said to sort of secular progressives, “You were worried about the religious right, just wait until you see the post religious right.” But we’re starting to see that around the world right now, where you have groups and movements on the right and on the left that have no pretense to Christian norms whatsoever. They care about Christianity only in terms of not something else, so that Christianity is just another way of saying Western Civilization, but there’s no commitment to the authority of the Bible, there’s no commitment to the New Birth, the teachings of Jesus and dicipleship and bearing the cross, and to the Holy Spirit. That is a terrifying thing in terms of a cultural movement.

On the other hand though, that is actually good news for the church and for the people of God. Because the way that the gospel goes forward is not through sameness with the culture around us. The way the Gospel goes forward is through distinction. And so when we think about evangelicalism, and we think about what does it usually mean when evangelicals themselves have said the word evangelical, it means commitment to the truthfulness and the authority of the Bible, commitment to the need for personal faith and repentance, commitment to the cross of Jesus Christ as the climax of all of creation and the place from which flows redemption. It’s a commitment to personal evangelism and to missions. Those things are still going to be here. There are some people who would say, “Well, evangelicalism isn’t even going to last.” Well, I think evangelicalism, whatever you call it, is going to last because the Gospel lasts, and because the church is always going to need that movement within it saying “Remember you cannot stand before God except through the mediation of Jesus Christ. Remember the gospel.”

So where does that leave us with the word evangelical? On the one hand, as I said, I’m tired of talking about this because I’m asked about it so often, and what I want to say is really there are deeper issues here that we ought to get at, the very root sort of questions about what it means to be Gospel people. That’s more important than what people think about when they hear the branding of the word evangelical. But it is a little disconcerting, because I’m afraid that if we’re not careful what happened to the word evangelist might happen to the word evangelical. Now, there’s a difference, because evangelist and evangelism, of course, are directly Biblical words. “Do the work of an evangelist.” But coming out of the the scandals of television evangelists in the 1980s, what I found was that there there were a lot of people, especially people under a certain age, who became very reluctant to use the word evangelism or evangelist. Even people who actually were evangelists, whether just in terms of having the gift of evangelism, or people who were actually vocationally evangelists, they were reluctant to use the word because they knew if they said it what what people would hear is “someone is fleecing you for money, someone who’s living a hypocritical moral life,” and those sorts of questions. Well, evangelist and evangelism are words we shouldn’t abandon to the hucksters, and evangelicalism isn’t something that we should abandon to cultural Christianity.

Now there are some words that just don’t mean the same thing that they used to mean. Billy Graham, who we mentioned earlier, came to the forefront through “Crusades.” Not many people use the word crusade right now, even Campus Crusade for Christ is “Cru.” Why? Because when people hear the word “crusade,” they typically aren’t thinking of what Billy Graham meant of a concerted spiritual warfare effort, they think the Crusades which which is not something that is a positive sort of association. So the word crusade is occasionally used, not much, that’s not that really much of a loss.

The word fundamentalist, if you think about the way fundamentalist used to be the shorthand for people who were Christians and who believed the basics, the fundamentals, the foundation points of the Christian faith. So if you asked someone in 1925, “Are you a fundamentalist?,” and if she said yes, what she’s saying to you is that she believes in the inerrancy of scripture, she believes that Jesus was was physically raised from the dead, bodily raised from the dead, she believes that Jesus will will return at the Second Coming, those foundational fundamentals of the faith. She believes in the Virgin Birth, those sorts of creedal questions that were coming under assault at the time. Now, and really starting sometime in the 1940s or so, fundamentalist started to be in many people’s minds – most people’s minds – shorthand for something else. So fundamentalist started to mean, in many contexts, well that you believe the King James Version is the only accurate translation of scripture in English, or you believe that pre-tribulation Rapture, or a dispensational reading of scripture is necessary, or certain sorts of codes about how long somebody’s hair should be, or what kind of clothes somebody should wear. And so people largely stopped using the word fundamentalist, and that became even more the case when we saw the rise of Islamic fundamentalism around the world, and fundamentalist started to mean to people “someone who is potentially violent.”

I don’t usually say that I am a fundamentalist, because although I do believe in the fundamentals of the faith, that’s not what most people are asking me. I can remember one time when I used the word for myself, and it was when I was in a really, really liberal gathering of people who were committed to the name “Christian” and they were asking me all of these questions about where I was, and where I stood, and I finally I said, “Look, what you need to understand is that I’m a fundamentalist.” What I meant was, what what I knew they would understand, is that I actually believe the Bible is true. I actually do think Jonah was swallowed by a fish. I actually think Isaiah wrote Isaiah. Those sorts of questions. But in almost every other situation, I wouldn’t use it because the shorthand doesn’t work for what I mean.

Well, evangelical is just shorthand. It’s a way of communicating really quickly what it is, what stream of professing Christianity that we’re in. So I don’t think we should give it up, at least not now. But I think we ought to use the word like a missionary. We all are missionaries, we’ve all been commissioned by Christ and sent forward. So we communicate with the shorthand, but we explain what the shorthand is. So for instance, I am an orthodox Christian, and what I mean by that is that I believe in classical Christian orthodoxy – the Nicene Creed and the Chalcedonian Creed and so forth. And so I may very well, in a shorthand sort of way, say “I’m an orthodox Christian.” I wouldn’t do that, though, if I were in Greece or in Russia. If I did, I would make sure that I was saying “I’m a small o orthodox Christian,” because in those contexts, when people hear that you’re orthodox they assume you mean “I’m part of the Greek Orthodox Church, or part of the Russian Orthodox Church. I believe in the doctrines of Eastern Orthodoxy,” Not what you mean – small o orthodox. In the same way, I’m a catholic Christian, but with a small c. When we’re reciting the Apostles Creed about the Holy Catholic church, or talking about the historic marks of the church is one Holy Catholic and Apostolic, I believe that. I believe the church is universal, the literal meaning of catholic. I believe that God’s people are unified, but I almost never would describe myself as a catholic, because what the average person would assume is that one means I’m a Roman Catholic, I agree with the doctrines of the Roman Catholic Church, or I’m in submission to the hierarchy of the Roman Catholic Church, which of course isn’t true.

The same thing has been the case over and over and over again throughout history. There was a time when, if someone is asking, “Are you a Lutheran?,” what they mean is “Do you agree with Martin Luther about the necessity of the reform of the church, and about justification through faith alone?” If that’s what someone meant, then I would be like, “Yeah, I’m a Lutheran, I’m with him on those things.” Typically now, what people mean is “Are you part of the Lutheran Church, are you part of the Lutheran movement?” There was a time when people would use the word Anabaptist, not just to apply to the groups that we know see as Anabaptists, but speaking of anybody who practices believer’s baptism. A re-baptizer, the word literally means, which was a slur that people just eventually adopted. It was shorthand, it worked sometimes, it didn’t work other times.

Same thing would be true with “I’m a Protestant Christian.” But if I’m in Northern Ireland, I’m going to explain what I mean when I say, “I’m a Protestant.” What I mean is not that I’m associated with some cultural faction within that country, what I mean is that I agree with the reformers about sola scriptura and justification through faith, and those reformational doctrines. But you know, the exact same thing is true, really, with the word “Christian.” When you say, I’m a Christian, you have to explain what you mean. Because if you’re sitting on a plane, and you simply say to someone “Are you a Christian?,” and the person says “Yes,” that really doesn’t tell you very much. If someone is defining Christian as “Well, I’m an American,” or “I was baptized when I was a baby and I’ve never given any thought to it again,” or “My parents belong to the Episcopal Church,” or however it is they’re defining Christian. What you have to say is, “Are you someone who has repented of sin, and placed your personal trust in Jesus Christ crucified and raised from the dead?” Those are the sorts of questions that you’re going to be asking. The shorthand has to be explained.

Same thing, I think, is true with the word evangelical. Now, what’s going to be critically important, though, is that those of us who are going to be evangelical insist upon the gospel as foundational to our use of the term. You can’t control what anybody else does, you can’t control what your neighbors think when they think evangelical, you can’t control what television commentators mean when they say evangelical, but you can explain what the gospel means, and what it means to be a Gospel Christian, an evangelical Christian.

So, I’m willing to work with all sorts of people on all sorts of things. I’ll work with Latter Day Saints, I’ll work with orthodox Jews, I’ll work with all sorts of groups of people, people who have no religious faith whatsoever. And I would even join a group that was, say, Citizens Against Abortion, or say, Citizens Against Human Trafficking, and so forth with those people. I wouldn’t join a group that was Christians fill-in-the-blank, because that would confuse what I mean when I say Christian in a way that is overheard by people who are asking, “What does it mean to be a Christian?” I would never be associated in terms of evangelical with, for instance, prosperity gospel teachers, who I don’t recognize as evangelical or as Christians. Health-and-wealth prosperity gospel, in all of its iterations, is not Christianity. It’s a different gospel, it’s a Cananite fertility religion that sends people to hell. It’s Baalism. I’m not going to accept that.

But at the same time, I’m not ready to give up the word evangelical. Evangelicalism will persist because the Gospel persists, and as a good evangelical, Martin Luther, might have put it: “Let goods and kindred go, the shorthand words also, the words they may confound, our hope is onward bound, His Kingdom is forever.” That’s loosely interpreted from the German. So, let’s keep the word evangelical as long as we can, but more importantly, let’s be evangelical. Let’s keep the Gospel.

This is Russell Moore, an evangelical Christian (not as seen on TV). Let me know what sorts of questions you have, and conversations you’d like to have on Signposts.