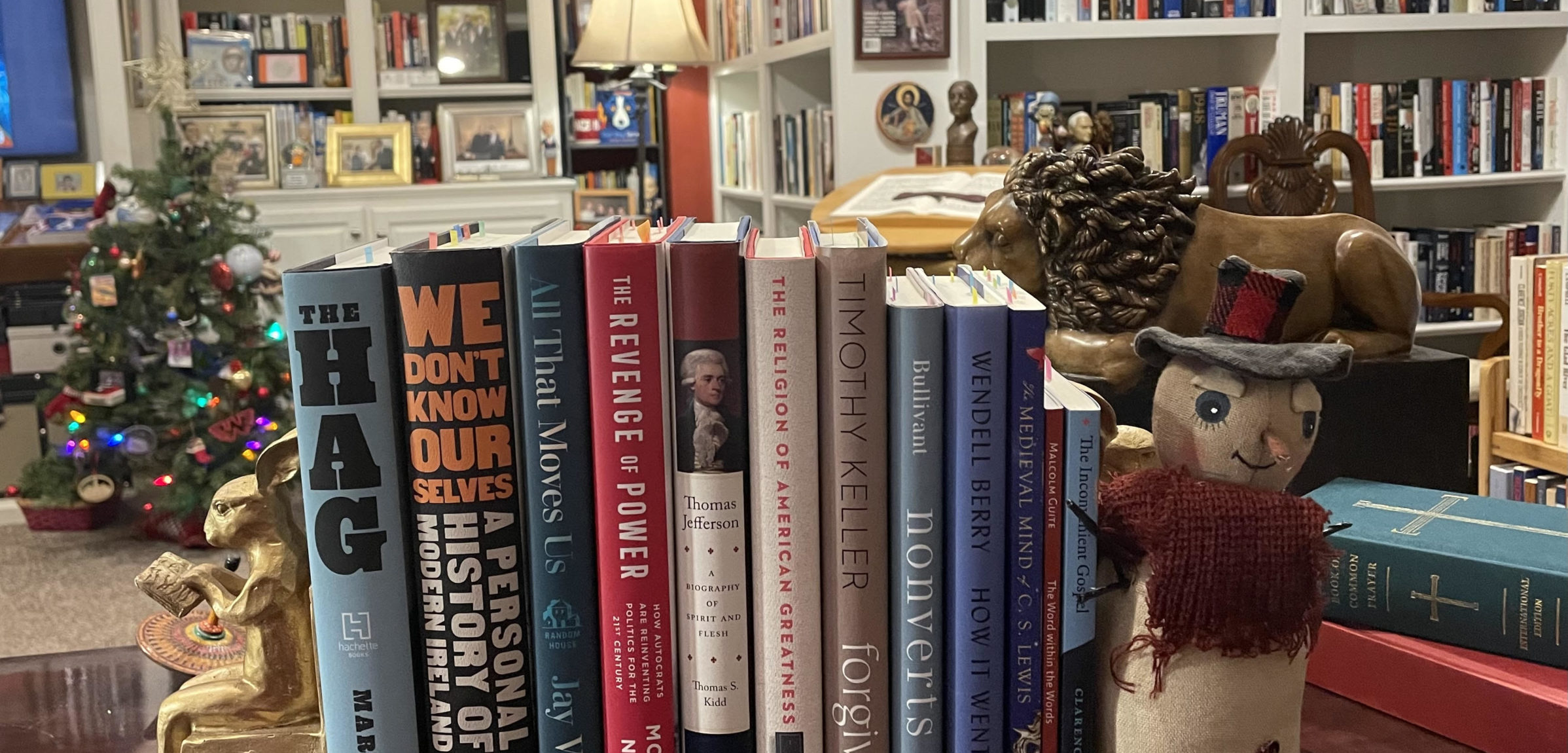

It’s December, so that means it’s time for the annotated list of my favorite books of the past year. All my usual caveats apply. These 12 books are in no particular order—just the order in which I pulled them off the shelf.

1. Malcolm Guite, The Word within the Words (Fortress)

Last year I sat around a fire at a friend’s house with his guest, the poet Malcolm Guite. Guite recited entire poems—his and others’—from memory and blew smoke rings from his pipe. I came home and told my wife, “I’ve never felt more like a hobbit.” (That’s saying something, since I feel like a hobbit much of the time and, occasionally, on a really bad day, an orc.)

This little book, less than 90 pages, is an articulation of Guite’s theology. Many such books become position papers of sterile syllogisms and axioms. Not this one. Guite writes, “My vocation as a poet attunes me particularly to the mysteries and beauties of language: the magic of words, the cadences and music of speech, but most of all, kindling and glimmering through all the words we use, the mystery of meaning itself and the wonderful vehicle of metaphor whereby one thing can be transfigured by the meaning of another.”

Guite asserts that his entire theology can be summed up in the prologue to the Gospel of John—showing how the “Word made flesh” informs how he reads the Bible, how he worships and prays. He discloses how reading the Psalms for a study on the “backgrounds” of medieval poetry changed him.

“Suddenly, reading Psalm 145, with the Bible open in my mind, I had an overwhelming awareness of God’s presence,” he says. “Perhaps it was triggered by those verses: ‘The Lord is nigh unto all them that call upon him, to all that call upon him in truth.’”

In reading this book, those who love poetry may find that they can love theology too. Those who love theology may feel the pull of poetry. And those of us who love both may find a guide in one who, like any good hobbit, knows the way not only to Mordor but also back to the Shire.

2. Timothy Keller, Forgive: Why Should I and How Can I? (Viking)

This book is classic Keller. He lays out various ways of understanding forgiveness, showing how many of them contradict themselves or lead to disastrous consequences. He deconstructs both the “cheap grace” that offers forgiveness without accountability and the quest for revenge that can easily consume a person, community, or culture. Keller also examines a view of forgiveness many hold and don’t recognize: a “transactional” approach that requires humiliation of the one seeking forgiveness.

The resurgent shame-and-honor culture, he writes, “either produces a heavily inquisitorial, merited-forgiveness approach or leads people to abandon forgiveness altogether.”

Yet the best part of the book is not cultural but personal. Keller teaches his readers to recognize how they may have internalized false views of forgiveness and vengeance, causing them to be more controlled by what others have done in the past than they think. “Hidden roots work in hidden ways,” he writes. “Unless you dig around to find them, you may never see them until they have sprouted and you have done or said something cruel that shocks you.”

Pointing to the old concept of the “wraith,” an ethereal wandering ghost, Keller warns, “If you don’t deal with your wrath through forgiveness, wrath can make you a wraith, turning you slowly but surely into a restless spirit, into someone who’s controlled by the past, someone who’s haunted.”

Again, in classic Keller fashion, he does not divide readers into “forgivers” to be praised and “unforgivers” to be shamed. He shows that true forgiveness is a problem for all of us. And he gives wise counsel for how anyone—even those who think they are too angry or numb to ever give or receive forgiveness—can move forward.

You can listen to Tim and me discuss this book and questions about how and why to forgive in this episode of my podcast.

3. Clarence Jordan The Inconvenient Gospel: A Southern Prophet Tackles War, Wealth, Race, and Religion (Plough)

A couple of years ago, this list featured the brilliant biography of Clarence Jordan by historian Frederick Downing. Now, The Inconvenient Gospel includes excerpts of Jordan’s own writings on subjects ranging from the Sermon on the Mount to idolatry to racial injustice to peacemaking to Bible reading.

Clarence Jordan was a Jim Crow–era white Southern Baptist preacher and a graduate of my alma mater, the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky. For years, I respected Jordan—as I would anyone who experienced firebombs and murder threats from the Ku Klux Klan—but I assumed that in a denomination with a two-party system forged by the controversies of generations past, he was part of the “other” tribe, not mine.

Over the past several years, I’ve reconsidered a lot of that. Yes, Jordan and I would differ on some things. I hold to verbal inspiration and inerrancy of Scripture, while he reflected more of the “dynamic” view of the Bible taught in his time at Southern. He would be much friendlier to modern historical-critical methods than I would. But he knew, taught, and lived out far more of the Bible than I ever have or ever will. This little book is a reminder of why I’ve come to love Jordan and why I admire the sort of courage, conviction, and grit I see in him.

Some argue that figures from the past—say, 18th- and 19th-century theologians and preachers who held people enslaved—were “men of their times” and thus cannot be fairly judged by present moral considerations. I won’t engage in that debate here, except to say that Clarence Jordan was one such person who called easy answers on this issue into question. Somehow, in a cultural ecosystem that said otherwise, he managed to see that things like white supremacy and segregation were, in the words of the apostle Paul, “not in step with the gospel” (Gal. 2:14, ESV). And he paid a price for it that few of us could even imagine.

Besides enduring threats of murder by the Klan and others, Jordan was excommunicated from his Baptist church in Americus, Georgia, for his work not only to oppose segregation but also to model—in the Deep South—an interracial, integrated cooperative farm. Referring to the ancient idea of the church as our mother, Jordan wrote:

The little Baptist church in which I grew up nurtured me. In its womb I learned the scriptures. I suckled at its breast. And the little church thought that it not only was my mother, but also my father. And when I had to go about my Father’s business, the church said, “No, son, you are piercing our hearts. We don’t want to give you up.” And when I finally persisted in going about my Father’s business, my mother, the church, renounced me.

In reading these excerpts, you may be surprised at how relevant they are to the present moment—especially in the ways we try to create an idol of God who will bless whatever sin and injustice our flesh or tribe expects us never to relinquish. “Now, we would turn a fellow out of our churches if he got drunk on liquor,” Jordan wrote. “But we will make a deacon out of him if he is drunk on money and tithes it.”

4. Wendell Berry, How It Went: Thirteen More Stories of the Port William Membership (Counterpoint)

A few years ago, a pastor friend asked me where he should begin in reading Wendell Berry’s fiction. I told him what I recommend to anyone who asks that question: Start with Jayber Crow or Hannah Coulter. I usually add that all of Berry’s books and stories set in the fictional Kentucky community of Port William share a continuity and many of the same characters, but one need not read them in a set order.

When I gave this advice to a college student once, he responded, “So the stories are all in a shared universe? Like the MCU?” He was referring, of course, to the Marvel Cinematic Universe, and I couldn’t help but smile, wondering what it would be like to explain that metaphor to Mr. Berry.

My pastor friend texted again the other day, saying that he had finished all the Port William stories and asking what I would recommend he read next. “Well,” I replied, “Mr. Berry just published a new book of 13 more Port William stories.”

That might be surprising. Wendell Berry is, after all, 88 years old. Who keeps writing at that age?

“It gets even better,” I went on. “That collection of stories is one of two books by him published this fall.” The other is his 528-page nonfiction work, The Need to Be Whole: Patriotism and the History of Prejudice, which discusses race, justice, community, history, and nationalism, among other things. The agrarian life must be good for the body as well as for the soul, because neither book suggests that Berry is slowing down.

Having read them both, I chose the fiction volume for this list. Readers of the rest of Berry’s stories will recognize some familiar names, such as Andy Catlett, and as elsewhere, the stories move back and forth through the timeline, from the 1930s to the present day. The first story sets a scene to which later ones will echo—about the change that happened to this small rural community after V-J Day, as the country moved into a post–World War II era that brought mechanization, mobility, and a loss of what Berry calls “membership.”

Membership is the common theme behind all these stories, and in that way, it is fully complementary with the argument in The Need to Be Whole. In the latter, Berry notes, for instance, how small agrarian communities combat polarization by the simple fact that neighbors need each other—or, at least, know that someday they will. This results in a kind of “prepaid forgiveness.” In the How It Went stories, Berry pictures this kind of prepayment in the lives of children, the elderly, and people at almost every stage of life in between.

The best story of the book, in my view, is “Dismemberment.” The title is a play on words, since it’s about Andy Catlett losing his right hand in a harvesting machine and then “waking up” from his self-pity and bitterness to see that he was isolating himself from what he needed to be whole: membership in the natural world, in Port William, and in the love of his family and friends.

5. Thomas S. Kidd, Thomas Jefferson: A Biography of Spirit and Flesh (Yale University Press)

Visiting Monticello or the Jefferson Memorial always makes me feel ambivalent and divided. On the one hand, here are monuments to the man who wrote words I cherish: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” On the other hand, this same man enslaved human beings and even, credible evidence suggests, used this ill-gained power to sexually abuse an enslaved young woman, Sally Hemings.

In one sense, this man did more for religious freedom than perhaps any other American, with the possible exception of James Madison. And yet this same man literally cut the miracles of Jesus out of his Bible.

That’s why it’s hard to find—much less write—a high-quality biography of Thomas Jefferson. How does one describe Jefferson’s life without reducing him either to a human museum of documents and ideas or to a human crime scene of hypocrisies and atrocities?

This year, Thomas Kidd, a historian at Baylor University, gave us a definitive biography of the American founder. As is typical with Kidd, the book embeds research rigor within a gripping read—a rare combination.

Kidd clearly seeks neither to deconstruct the Declaration of Independence nor to whitewash Jefferson’s moral crimes and misdemeanors. He also avoids allowing the era’s historical events to obscure the personal reality of Jefferson as a human being. Perhaps this is most evident in the book’s descriptions of the rough and rocky relationship between Jefferson and his “frenemy” John Adams.

On the question of the Missouri Compromise, Kidd quotes Jefferson as writing of slavery, “As it is, we have the wolf by the ear, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go. Justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other.”

I came away from this biography viewing Jefferson as an unlikeable figure, but that’s because he was, well, an unlikeable figure in many ways. Yet he was not a boring figure. Kidd tells his story in a way that keeps readers turning the pages and finding all sorts of angles to the founder’s life that another historian might miss.

After reading this biography, I will still stand ambivalent and divided at the Jefferson Memorial. But I understand better than ever how Jefferson himself was, as Kris Kristofferson would put it, “a walking contradiction, partly truth and partly fiction.”

6. Moisés Naim, The Revenge of Power: How Autocrats Are Reinventing Politics for the 21st Century (St. Martin’s)

This book looks at the rise of authoritarianism around the world and finds a common formula autocrats use that is summed up in three words: populism, polarization, and post-truth.

Naim analyzes how celebrity functions for these aspiring authoritarians, who are not leaders with followers so much as stars with fans. “Fans build their personal identity out of a primal identification with the stars they follow,” he writes. “But they also build it in opposition to—and in hatred of—‘the other team.’”

Blurring the line between politics and entertainment does away with norms and guardrails that previously would have hemmed leaders in from their worst instincts. “Their fans have so much of their identities invested in the leaders that they cannot allow them to fail,” Naim notes. “When traditional politicians break an important norm, their supporters turn on them, and their political standing suffers. But when celebrity leaders break an important norm, their fans don’t turn on the leaders; they turn on the norm.”

The harnessing of resentment and desire for revenge, along with the populist celebrities’ denunciations of “elites” and “experts,” lead to a hollowing out of institutions and then to—in Naim’s words—a “kakistocracy: rule by the very worst a society has to offer.” As a result of all this, normal, everyday people withdraw from leadership or from the system altogether.

The book is meant to explain civic political realities, and it does. But I found it also eerily reflected the realities of church life—from the phenomena described in The Rise and Fall of Mars Hill to the implosion of several major denominations. This book not only lays out the stakes of what happens when these “three Ps” predominate but also counsels us on ways to counteract them.

7. Paul D. Miller, The Religion of American Greatness: What’s Wrong with Christian Nationalism (IVP Academic)

Many have noted the strange trajectory of Christian nationalism in recent years. At first, proponents’ typical response was to say there was no such thing as Christian nationalism, that the designation itself was just a slur by the Left. Then, many of these same people claimed Christian nationalism as an overt but misunderstood title. Many then proceeded to explain what they meant—with all of the illiberal and racialist features that opponents of Christian nationalism had warned about from the beginning.

While Christian nationalism poses obvious threats to democracy here and around the world, I am just as concerned about what it does to the people who embrace it. In the past couple of years, we’ve seen the way evangelicalism’s culture-war entrepreneurs have marshaled a niche of angry, unmentored, undiscipled young people with the “aren’t we naughty?” ethos of white Christian nationalism, combined with a rage against authority embedded in a cosplayed authoritarianism.

I can think of no one better equipped to write about Christian nationalism than Paul Miller, a professor of international relations at Georgetown University and a longtime, respected expert on national security and foreign policy.

In the book, he demonstrates the difference between patriotism and nationalism. He defends the ideals of liberal democracy and ordered liberty from a biblical, evangelical standpoint and dismantles plank by plank the illiberal, authoritarian, culturally “Christian” arguments for Christian nationalism. The book will help you understand where this viewpoint came from, what it does, and how to see the beauty of the alternative of the actual gospel—of a free church in a free state.

8. Fintan O’Toole, We Don’t Know Ourselves: A Personal History of Modern Ireland (Liveright)

This is one book that perhaps I should have waited until 2023 to read. Many of the subjects covered here are still too fresh in my mind, having experienced for several years the backlash from efforts to identify church sexual abuse and to reform the structures that cover it up. My context was Bible Belt American Christianity, not Irish Catholicism, but the uncanny parallels made me wince as I read this book.

The author shows the transformation of Ireland, at an unprecedented velocity, from culturally conservative Catholic enclave to a much more typical European secularization. In some other European countries, this happened in a slow “disenchantment” from the supernatural. But much of the faster Irish evolution, journalist Fintan O’Toole argues, was in response to the revelations about moral hypocrisy, sexual abuse, and cover-up in the Irish Catholic church.

In describing the various political and cultural changes in Ireland, O’Toole illustrates the state of the church with shockingly perverse details, such as parents bringing their children to apologize to the very priests who molested the children.

“This was the church’s great achievement in Ireland,” O’Toole writes. “It had so successfully disabled a society’s capacity to think for itself about right and wrong that it was the parents of an abused child, not the bishop who enabled that abuse, who were ‘quite apologetic.’

“It had managed to create a flock who, in the face of an outrageous violation of truth, would be concerned as much about the abuser as about those he had abused and might abuse in the future,” he continues. “It had inserted its system of control and power so deeply into the minds of the faithful that they could scarcely even feel angry about the perpetration of disgusting crimes on their own children.”

The people could not withstand what O’Toole calls the “most shocking realization of all”—namely, “the recognition by most of the faithful that they were in fact much holier than their preachers, that they had a clearer sense of right and wrong, a more honest and intimate sense of love and compassion and decency.”

I wrote more about this book in the May 12, 2022, newsletter. You can find that essay here.

This is not a fun book to read. But it’s an important, sobering reality check at a time in which Bible Belt Christianity could find itself in a situation similar to the Irish Catholic church of not so long ago—as a political and cultural juggernaut exerting influence but without the necessary moral credibility to convince a new generation that its message is good, true, and beautiful.

9. Stephen Bullivant, Nonverts: The Making of Ex-Christian America (Oxford University Press)

The subtitle of this book could be a bit misleading. Bullivant is arguing neither that America itself is ex-Christian nor that religion is going away in the United States. Rather, he is arguing that the massive population shift toward the religiously unaffiliated—often referred to as “nones”—will have consequences far beyond the boundaries of the church.

More specifically, Bullivant writes not about those who have never had religious faith but of what he calls “nonverts”—those who were previously practicing their faith but have “deconverted.” The nonreligious and the ex-religious are not the same, he contends, any more than an ex-spouse is the same as anyone to whom you are not married. Or, to use another of his analogies, someone who is a recovering alcoholic is in a different category than a lifelong teetotaler.

This book intersects with topics I’ve discussed in this newsletter (such as our conversation about the implications of the Ravi Zacharias and other evangelical scandals). But it uses a metaphor I can’t believe I’d never thought about: what Bullivant calls the “Harper Valley Effect,” riffing off Jeannie C. Riley’s classic country song “Harper Valley PTA.”

The issue, Bullivant argues, is not that some religious leaders fall to the desires of the flesh. It’s that, in the most damaging of these cases, there are boards, congregations, denominations, or colleagues covering up the scandals, leading to the (reasonable) conclusion for some that the whole system is corrupt.

In his discussion of the decline of mainline Protestantism, as opposed to evangelical Christianity or the Latter-day Saints, Bullivant points out how a deemphasis on evangelism contributed to a much more precipitous capsizing of those churches. It’s not just that evangelism can, at its best, bring in new converts to a faith, he argues, but that it is “critical for retaining the born-and-raiseds you already have.”

“If a church doesn’t inculcate in its members the feeling that what they have is something that’s worth sharing with others—or at least trying to—then it sends the message that perhaps it’s not so essential for me either,” he continues. For example, he interviewed two Latter-day Saints missionaries who, well into their requisite service, had yet to make a single convert. But that didn’t mean their mission had failed, Bullivant notes. The very acts of sharing their faith and serving their church served to bond them with their religion.

I suspect that we evangelicals will see that our overreaction to what some viewed as overly programmed evangelism training (teaching teenagers and young adults to talk about the “four spiritual laws” or the “Roman Road” to salvation) will further prove this thesis.

The book makes an interesting claim that “MAGA Christianity” and the viewpoints that Rod Dreher and I offer (which I would claim are quite different, but I see how Bullivant could categorize them together for his purposes) are actually rooted in the same sense of a decline of cultural Christianity—just with very different senses of what such a decline means and how to reverse it.

I expect I will give this book out to many people who want to understand the difference between the unchurched and the de-churched and the implications that difference has for reforming our witness, our discipleship, and our integrity.

10. Marc Eliot, The Hag: The Life, Times, and Music of Merle Haggard (Hachette)

Back when I was a denominational bureaucrat, I once skipped a Southern Baptist Convention Executive Committee to attend a Merle Haggard concert at the Ryman Auditorium right down Broadway from the Baptist building. I say that with a great deal of contrition, shame, and regret. I wish now that I had missed far more SBC Executive Committee meetings to attend Merle Haggard concerts.

The opening pages of this new biography of Haggard include a quote from the singer: “The difference between country music in Nashville and country music in [Bakersfield] is that country music in Nashville came out of the church. Country music in California came out of the honky-tonks and bars … and from the soil. … It was more about pleasing a bunch of drunks than it was singing for a choir.”

The biography examines how Haggard, like Thomas Jefferson, was something of a walking contradiction. He sang “The Fightin’ Side of Me,” a repudiation of the anti–Vietnam War counterculture, yet stood up for the Dixie Chicks when they were canceled for opposing the Iraq War. In his most famous song, “Okie from Muskogee,” Haggard sang, “We don’t smoke marijuana in Muskogee,” but he regularly smoked marijuana from 1981 on. In fact, Eliot points out that when a reporter asked about rumors of his pot usage, Haggard responded, “Son, the only place I don’t smoke it is in Muskogee.”

Eliot shows both the musical genius and the cantankerous personal side of Haggard. When a studio executive wanted him to redo a song recording because “it doesn’t sound enough like Merle Haggard,” the singer shot back, “Who the hell did he think was in that studio? Taylor Swift?” The tragic aspects of Haggard’s life and choices aren’t hidden here. But neither is the sense of a haunted man who really wanted to love his mother (“Mama Tried”), yearned to be a good son of an Okie father, and found himself falling short again and again of his own best intentions.

The Haggard story is important, even for people who don’t like country music, because he intersects so many of the most important cultural moments of the 20th century. The cast of characters in this biography includes Richard Nixon, George Wallace, Barack Obama, Bob Dylan, and on and on. If you’re interested in Haggard, read this along with David Cantwell’s excellent Merle Haggard: The Running Kind.

If you want to listen to Haggard’s music and haven’t before, start with these: “Mama Tried,” “Sing Me Back Home,” “If We Make It Through December,” “Are the Good Times Really Over,” and his cover of Iris DeMent’s “No Time to Cry,” as well as his duet with Willie Nelson (recorded in one take in the middle of the night) of Townes Van Zandt’s “Pancho and Lefty.” I’m also partial to his version of “Footlights,” sung alongside George Jones.

11. Jay Wellons, All That Moves Us: A Pediatric Neurosurgeon, His Young Patients, and Their Stories of Grace and Resilience (Random House)

Sometimes circumstances prompt one to read a book one would never have chosen otherwise. I know nothing at all about medicine, much less about pediatric neurosurgery. So in every other circumstance, I would have skipped over this book, assuming it was for someone else.

But the author’s wife is a friend I met some 30(!) years ago when we both interned for United States Rep. Gene Taylor, for whom I worked for four years at the start of my career. When I saw that Melissa’s husband (whom I hadn’t met at the time) had written a book, I picked up a copy. I’m glad I did.

This book is about far more than describing the complexities of surgery or stitching together inspiring stories of resilient children and their parents. Wellons, a medical professor and surgeon at Vanderbilt, writes movingly about the mysterious intricacy of the human brain and the toll of trauma.

Of the near epidemic of burnout in the high-stakes field of neurosurgery, Wellons writes, “It’s dangerous. Add a chronic lack of sleep and an environment of probing and second-guessing, and you can begin to lose trust in everyone around you. The constant beat of life-and-death decisions begins to change you in fundamental ways. Trust gives way to suspicion; care gives way to loathing.” This tracks very closely with what I’m seeing right now in Christian ministry.

Wellons writes of his upbringing in Columbia, Mississippi, where his family attended the local 16-member Episcopal church. “The only other child in the church and I both took Sunday school classes with the adults,” he writes. “He and I knew the word ‘eschatology’ by the sixth grade.” He brings the perspective of someone still rooted through memory to this community while acknowledging, with Thomas Wolfe, that one can’t go home again.

This book reminded me of the hopeful aspects of the human spirit and gave me insights not only into my friends in the medical profession but also into my own life and work. I’m glad I “accidentally” happened upon it.

12. Jason M. Baxter, The Medieval Mind of C. S. Lewis: How Great Books Shaped a Great Mind (IVP Academic)

Medieval is a complicated word in this second decade of the 21st century. A handful of Catholic integralists offer blueprints of a society based on an imaginary rendering of medieval Christendom. At the same time, many people think medieval is merely a slur meaning “backward or primitive.” Yet this book shows how one of the most important Christian thinkers of our era was shaped and formed by medieval thought.

Humanities professor Jason Baxter argues that this is why Lewis, unlike almost any other figure, could address the meaning of human longings. In the mechanized, quantifiable cosmos of modern thought, others dismiss these longings as simply “emotions.”

“In modernity, human beings prefer to describe rocks as falling in obedience to a law, whereas medieval people spoke of the rock as desiring, longing to return to its natural place, like a pigeon flying back to its nest by a homing instinct,” Baxter writes. “In this way, the medieval cosmos, saturated with presence and soul, was densely alive and exerted a moral pull on the soul and mind.”

The sacramental medieval vision of the universe Lewis inhabited, this book shows, is part of what enabled him to join imagination and reason, longing and objectivity, myth and truth, the known and the numinous. The author explains such influences as Dante, Boethius, Otto, and Buber in ways that are accessible to those who aren’t familiar with them.

This book can help shake you out of the disenchantment of the modern age—a disenchantment that, as Charles Taylor demonstrated, affects us all. And it reveals why the world Lewis showed us through the wardrobe was able to surprise us with joy.

This post was first published in Moore to the Point. Subscribe to get the latest content from Russell Moore in your inbox.