This piece was adapted from Russell Moore’s newsletter. Subscribe here.

Nothing can provoke anger quicker than mercy, when it’s directed to the wrong kind of people.

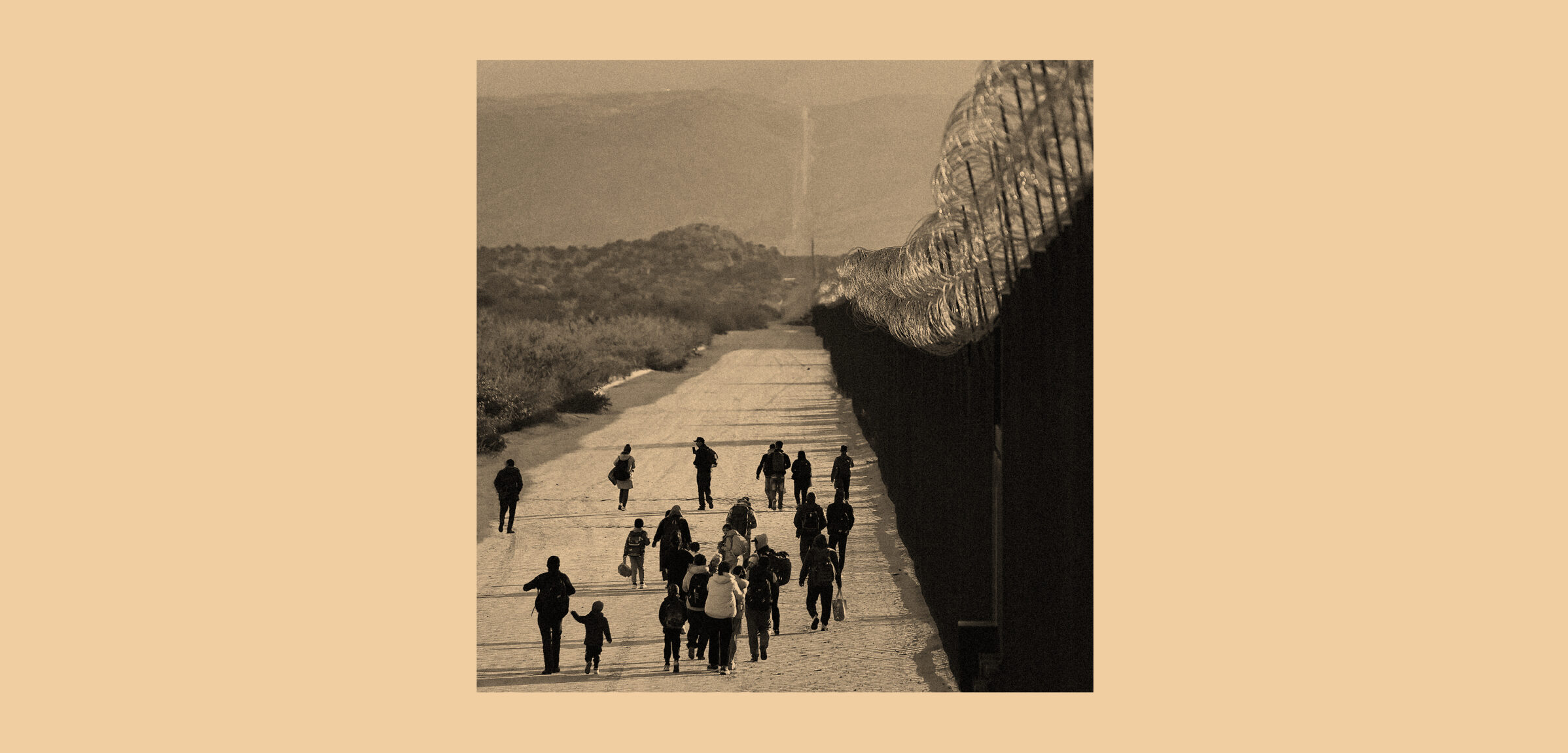

Marking the church’s Year of Jubilee, Pope Leo XIV invoked biblical language calling for kindness to migrants as human beings made in the image of God. There’s nothing the least bit controversial about this. It’s what the Bible says, what Christians have always believed, what official Catholic teaching makes explicit. The pope did not call for countries to stop enforcing their borders, nor did he give any specific policy proposals for how a nation should best balance security and mercy. He simply called on Christians to refuse harshness or mistreatment of vulnerable people.

Some people didn’t like this.

The blowback the pope received was not from fellow bishops or clergy or, as far as I know, from any large numbers of churchgoing Roman Catholics. Instead, political activists and social media conflict entrepreneurs blasted him, not so much for what he said as for the fact that he spoke to the issue at all.

Difficulty speaking to immigration is not a specifically Catholic problem—in fact, it may be more of a problem for other Christian groups. After all, every pope in recent years and many bishops have spoken consistently to this point. And, of course, the pope is the pope. He can’t be fired the way the pastor of a storefront Bible church in Aurora, Illinois, or Athens, Alabama, can. Some of these pastors are trying to figure out how to care for people in their communities who want to hear the gospel but are fearful of being arrested by immigration officials on their way to church.

This is not a simple matter of “Well, people who broke the law should be accountable.” Some of these people are following the right process—but may be unable to show up for court to adjudicate their cases for fear of being arrested in line. Some of them have broken no laws at all; they are Americans but have someone in their household, maybe a mother or a father, who is not. And some of them were doing everything right—filling out the right documents, working to provide for their families—when their asylum claims or refugee status was abruptly withdrawn.

One pastor said to me, “Most of my people want to know how best to pray for and to serve their neighbors here, but if I answer their questions from the pulpit, a small minority of the congregation is going to say that I’m ‘supporting illegals.’” One preacher, an immigration hawk who supports mass deportation, said he has the same problem when he tells people the church’s job is to minister to everybody, regardless of where they’re from or what they’ve done. Yet another minister confessed, “I don’t even know what my views on immigration or ICE are; I’m not trying to weigh in on that. I just want to remind people to love their neighbors, full stop. That’s Jesus. How is that controversial?”

Well, it turns out Jesus is very controversial—and always has been.

As a matter of fact, when it comes to the language of Jubilee, Jesus kept preaching until he reached the point where his hearers were outraged, for all the same reasons we see today.

In his hometown synagogue, Jesus turned to the scroll of Isaiah and read a passage that echoes directly the language of Jubilee from the Torah: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to proclaim good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim liberty to the captives and recovering of sight to the blind, to set at liberty those who are oppressed, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor” (Luke 4:18–19, ESV throughout). This reading was not controversial—even when Jesus made the audacious claim “Today this Scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing” (v. 21).

Luke recounts, “And all spoke well of him and marveled at the gracious words that were coming from his mouth” (v. 22).

Most of us would call it a day and leave the teaching at this level of abstraction. Jesus, though, knew the applause meant they didn’t really get what he was saying. They wanted Jubilee for the poor and the captive so far as it applied to them, struggling people in an impoverished backwater of an occupied Roman territory.

But Jesus kept talking and implied this mercy of God applied even to people they didn’t like. He referenced from the Bible that the great prophet Elijah was sent to care not for one of his own people but for a Canaanite widow outside the borders of Israel. Jesus then pointed out, even more harshly, that Elisha bypassed countless Israelites with leprosy to heal a foreigner—not just a foreigner but a Syrian, and not just a Syrian but a Syrian soldier.

Again, Jesus did not even apply these scriptural principles at this point. He simply pointed out what the Bible had said. But “when they heard these things, all in the synagogue were filled with wrath” (v. 28).

Jesus did not bumble into this crisis accidentally. He knew exactly what he was doing—and walked right toward it. Mercy destabilizes the moral bookkeeping of who is “deserving” of it. That’s true for all of us, and our responsibility is to keep hearing the Word of God until it reaches where we do not want it to go, where our passions rise up and say, “No, not that far.”

The Bible does not give a comprehensive public policy for migration or asylum. Christians of good faith can disagree on those things. But the Bible does give a comprehensive view on what we are to think of human beings, including migrants. The church has a mission to shape consciences around how we minister to scared and vulnerable people, regardless of whether we think they should have stayed somewhere else. And Jesus has already taken the question of “Who is my neighbor?” off the table (10:29).

What Jesus did with Jubilee is radically shocking. He took a year out of the calendar and announced it was pointing not to a date but to a person—to him. He is the kingdom. He is the deliverance. He is the Jubilee. What’s dangerous about this is not where it’s complicated (What counsel do I give someone who is illegally here but in danger back home and has nowhere else to go?). What’s dangerous is where it’s very, very clear—because it asks us whether our deepest loyalties are still capable of being interrupted by the Word of God.

The question is not whether the Bible is clear enough but whether we are still capable of being changed by it. That was controversial in Nazareth then. It’s controversial in Nairobi or Naples or Nashville now.