As of yesterday, I know why the most depressing sound on earth to me is the sound of CBS News’ 60 Minutes stopwatch.

As a child and a teenager, Sundays were a blur of activity. Sunday school assembly at 9:30 AM, Sunday school at 9:45, worship service at 11:00, Training Union (then Church Training, then Discipleship Training, then whatever they called it next) at 6, worship service at 7, and then some kind of youth group activity after the service. Often I was running late for Training Union and would catch, as I was leaving the house, the intro to 60 Minutes with that stopwatch ticking away. To this day, I cringe when I hear that sound.

Yesterday, guest-hosting the “Albert Mohler Program,” I invited historian Craig Harline on the program to talk about his new book, Sunday: A History of the First Day from Babylonia to the Super Bowl (Doubleday). Harline spoke of something called “Sunday neurosis,” a sense of profound sadness that comes over some people on Sunday. It’s the type of melancholy one hears in Kris Kristofferson’s “Sunday Morning Comin’ Down.” Because the routine is disrupted, one falls into an adrenalin-starved mild depression. But the opposite is also true, he says; there are some people who so love Sunday, for whatever reason, that they are mildly depressed at the thought of ending. For Harline, there’s a lot bound up in these disparate reactions to a day.

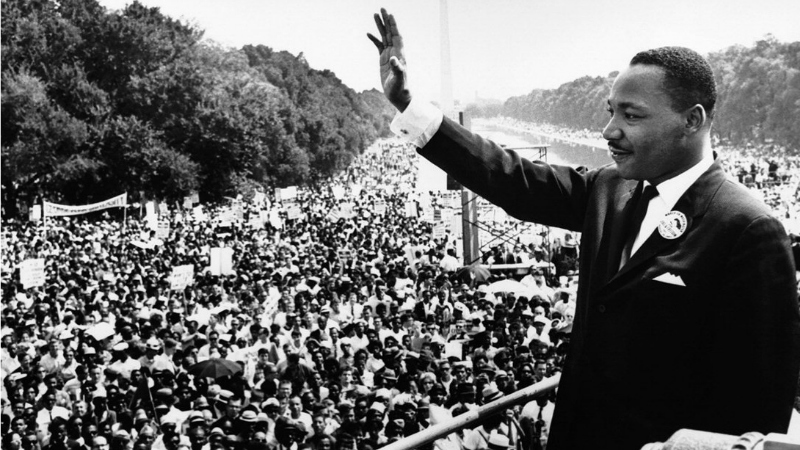

Harline’s overall thesis is that, “as the world changes, Sunday changes.” He demonstrates this through medieval, Reformation, and Puritan debates over the Sabbath, 20th century skirmishes over “blue laws,” and the contemporary scene of an American culture in which sports, both amateur and professional, will have no gods before them on the First Day.

This is a fascinating discussion to me, though not because of the perennial debates between Christians as to whether the Sabbath is fulfilled in Christ or in the Lord’s Day. Most Christians believe there is something distinct about the Lord’s Day as a weekly Easter victory celebration of the resurrection of Christ Jesus.

And yet, it does appear that Sunday has changed, even for the most conservative evangelical Christians. That’s not entirely a bad thing. In my hometown, men who would get drunk on Saturday nights and women who would gossip all day every day at the local beauty shop would never mow grass on a Sunday, simply because it would look trashier to the neighbors than an unmown yard. That’s not a Christian understanding of the Lord’s Day. Nor should we adopt a dour hyper-Puritan view of the Lord’s Day in which the central point is what we cannot do on that day.

Still, Harline is right. Sundays have changed, even for Christians, but this change has not been because of an ongoing discussion of the scriptural teaching on the Lord’s Day. Instead it seems that Christians don’t even think about the uniqueness of Sunday, as we rush ourselves off to the early service so we can get to T-ball practice on time. We don’t have to agree about how the Sabbath fits or doesn’t with the Lord’s Day, and we shouldn’t bind each others’ consciences (one way or the other) with a lot of particular dos and don’ts of Sunday observance.

But if we’re going to alter the way we observe Sunday, shouldn’t it be intentionally? Shouldn’t it be through meditation on the Word of God rather than simply through the osmosis of an American engine of commerce that would much rather see our adrenalin surge because of the Super Bowl than the empty tomb?

My home church did something right, I think. That 60 Minutes stopwatch was cloying to me not because I find Andy Rooney annoying (though I do). It probably was instead that I knew Sunday was coming to an end, and then it is back to the “normal” time of “six days you shall labor.” Tick, tick, tick, tick…